Lifewide Magazine #19 is focusing on the concept of mental time travel. The very idea of time is a question that scientists and philosophers have struggled to understand and once we start talking about physically travelling through time we enter the realms of science fiction and quantum physics. But we all have the capacity to think our way back to moments in time that we have experienced as we access our memories, both clear and not so clear, of past events in our lives. Being able to look back and recreate mental images of those moments and imagine the future is something that is fundamental to who we are and when we lose this capacity for mental time travel we lose ourself.

In this issue of the magazine we invite readers to consider the possibility that in life we indeed make use of the skill of mental time travel from a very young age. Psychologists and neuroscientists tell us that we start this process from the age of 3 when we begin to develop, along with language, the capacity to create and imagine worlds, full of fantasy and adventure. And we continue to enjoy this amazing capacity to access memory and create mental imagery throughout our life span. One could argue that it aids our innate compass which is directing our attention to what we need to understand and feel, in order to become the best version of ourselves, drawing on past versions of ourselves and imagining what might be in the future.

But life is not always full of happiness and joy: it may also contain moments and events that are extremely challenging, difficult, stressful, sad or emotionally complex and traumatic. In such circumstances we might avoid or deeply bury our memories and creatively use our imaginative abilities in our present to escape from our painful past. In such circumstances we may seek help from trained professionals in the fields of psychotherapy, trauma therapy or hypnotherapy to help us live with our past and motivate us to live our lives, with the least risk and damage possible, always growing into better versions of ourselves?

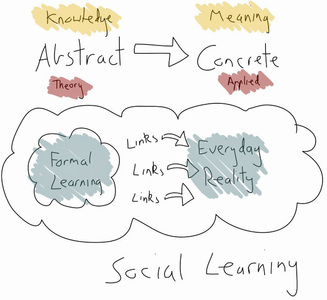

Human beings are meaning making creatures. We enjoy creating meaning that resonates with our authentic selves. Meaning helps us feel we have a purpose and through our relationships and what we do, that we are fulfilling these purposes. We know when this meaning is resonant. It feels right.

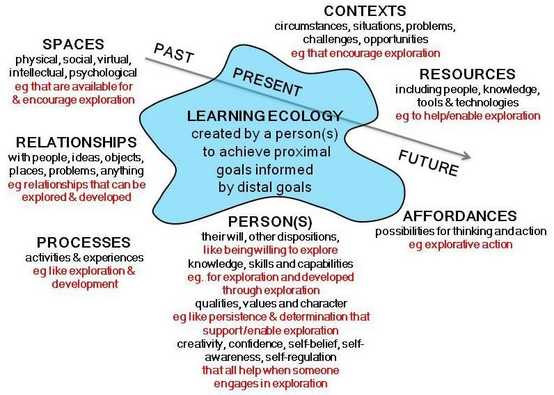

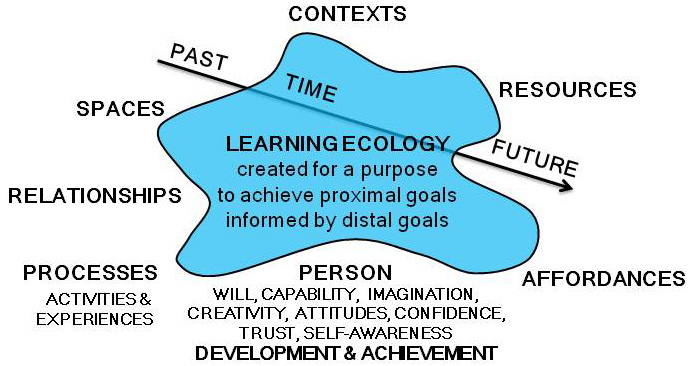

All the authors in this issue of the magazine have embarked on rich and thought-provoking journeys. They share their learning (their making of meaning) and experiences in travelling mentally through time. This has required re-connecting and engaging mentally, cognitively, physically, emotionally and spiritually with themselves and creating their own ecologies in the present to assist themselves in their journey to their past. Contributors have shared their vulnerabilities and their willingness to connect with sometimes painful memories and experiences and in this process revealed things which are deeply personal, in order to help us, the reader, develop deeper understandings about the strategies and tools we use to help us connect to the past from our present.

Through the articles in this issue I am reminded once more that human beings have indeed a much more diverse pallet of knowing and wisdom. What is echoed on all the contributions to this issue is the sense of “becoming’’ somebody more enriched as a result of self-exploration .No matter what the journey, in order to reach to our own unique treasures, we are required to demonstrate an ability to be willing and playful learner, curious and open to reflect, courageous to connect, process and tolerate uncertainty in order to formulate new meanings. All skills and attributes shown by our authors. What is an over arching theme, albeit not explicitly pointed out, is the creativity which is underlying the way they lived and worked through their experiences. This manifested in the stories through an inextricable link between their memories, spaces and places and the imaginative use of those memories to alter the feelings and perceptions they held for themselves and their lives; Perhaps we could argue that creativity and use of imagination is an inherent life force, an essential ingredient in forming and fulfilling our purpose.

Maria Kefalogianni

GUEST EDITOR #19

RSS Feed

RSS Feed