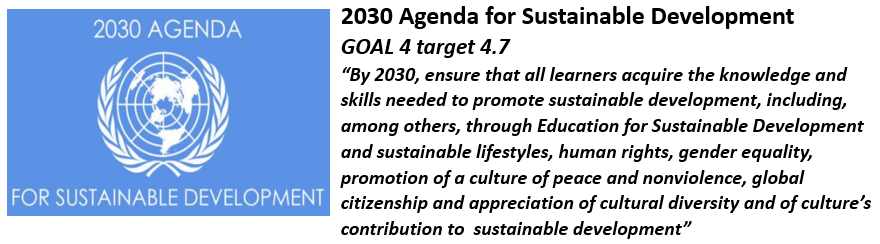

The Education for Sustainable Development Roadmap was published in 2020. It defines 5 priority areas for member states to support and implement ESD. They are urged to:

1 integrate ESD in global, regional, national and local policies related to education and sustainable development.

2 promote whole-institution approaches to ESD

3 help educators develop the knowledge, skills, values and attitudes needed for the transition to sustainability.

4 recognize and engage young people as key actors in addressing sustainability challenges

5 engage communities as they are where meaningful transformative actions are most likely to occur.

The report argues that ESD aims to do three things:

1 raises the awareness of the 17 goals in education settings:

2 promote critical and contextualized understanding of the SDGs

3 mobilize action towards the achievement of the SDGs

Yesterday there was a debate in the UK parliment about embedding ESD in the English National Curriculum. Here is Lord Jim Knight leading a debate in the House of Lords.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed